Passkeys at a Glance

Passkeys are pushed as an alternative for passwords by many modern websites and big players such as Google, Apple and Microsoft. But WTF are passkeys actually? As is often the case when new standards enter the market, participants tend to play fast & loose with the terminology making it more confusing for everyone.

Main point: passkeys are asymmetric cryptography (public and private keys) plus key management on top. Think SSH keys, but the passkey protocol also handles uploading the public key to the service provider and securely maintains the private key. It removes the weaknesses of people choosing their own passwords by replacing it with a structured protocol of how to generate secrets without burdening the Mr. Average Joe.

This gross oversimplification is a good starting point, but I’m intentionally vague about the details because that’s where companies and their marketing make things complicated.

Passkeys are powered by FIDO2 and the WebAuthn standards. A core component is an “authenticator” - the hardware or software thing that stores the cryptographic keys. The standard distinguishes how authenticators can exist in the world:

A platform authenticator

A platform authenticator is attached using a client device-specific transport, called platform attachment, and is usually not removable from the client device.

and a roaming authenticator

A roaming authenticator is attached using cross-platform transports, called cross-platform attachment. Authenticators of this class are removable from, and can “roam” between, client devices

In other words, your Android/iPhone is a platform authenticator while your YubiKey is a roaming authenticator.1

This distinction is called “authenticator attachment modality” and it is one of three dimensions describing different types of authenticators. The other two are (a) whether the authenticator can verify the user (“authentication factor capability”) - aka ask for a PIN or fingerprint, and (b) whether the authenticator’s credentials are discoverable (“credential storage modality”) - aka whether you need to provide a username.

Depending on where an authenticator falls in this classification system, it can be used for second-factor authentication, passwordless (replacing a password), or usernameless (replacing everything!)

This is where marketing confusion starts: officially, “passkey” refers to discoverable (usernameless) authenticators. However, the term is often used for anything related to WebAuthn, which leads to unmet expectations and surprises:

Unfortunately, many recent introductions of “passkeys” are actually misnamed implementations of non-discoverable security credentials. You may be prompted to “create a passkey,” but when you look in your password manager, there’s no passkey for that website. You can log in using the specific device where you created the software security key, but you have to enter a username (and maybe a password), and there’s no passkey to sync or manage.

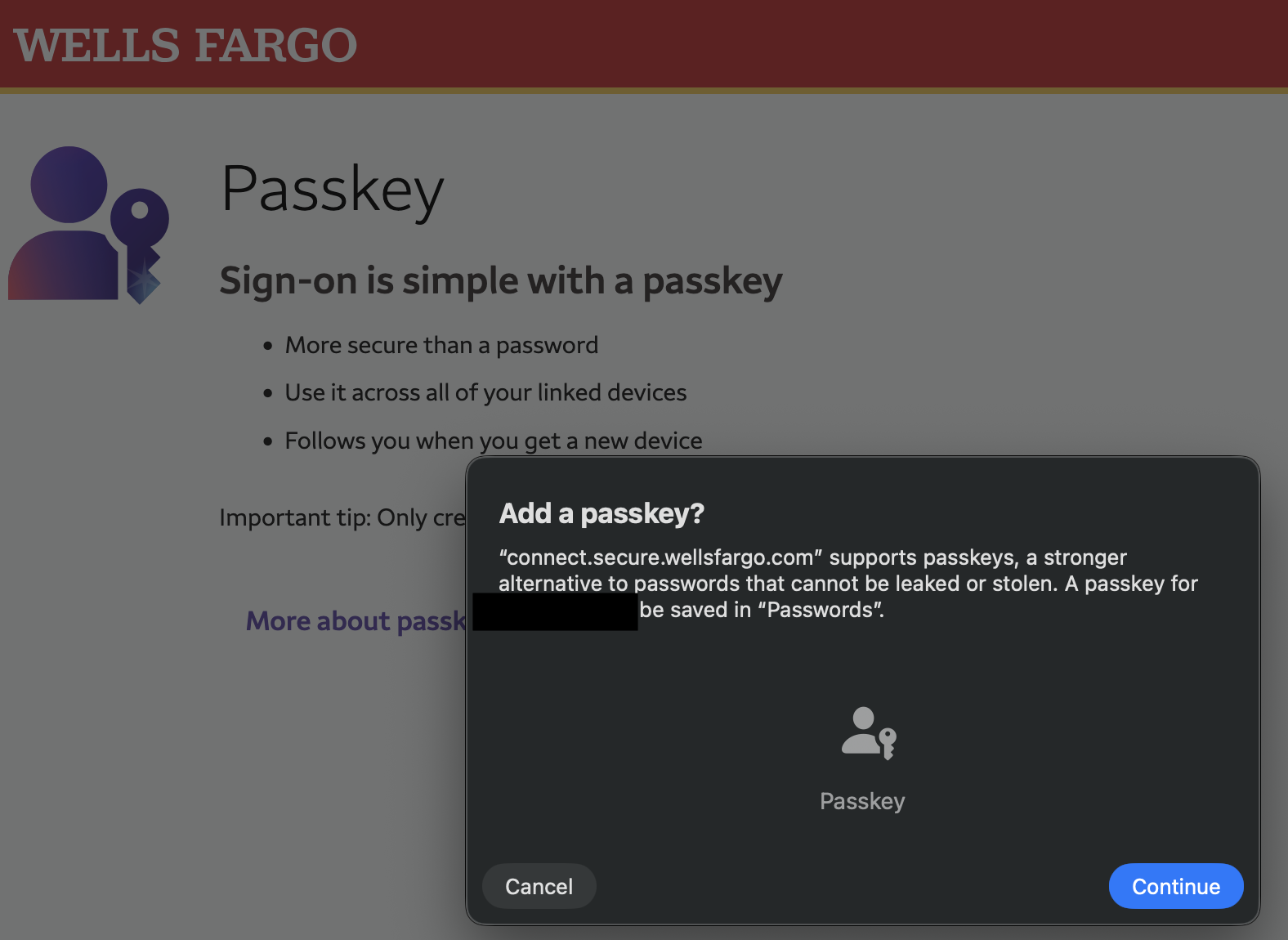

Moreover, the standard allows service providers to prefer certain authenticators, as shown in this example flow. So, a YubiKey might be useless if a service provider doesn’t accept roaming authenticators. As of November 2025, Wells Fargo is a good example:

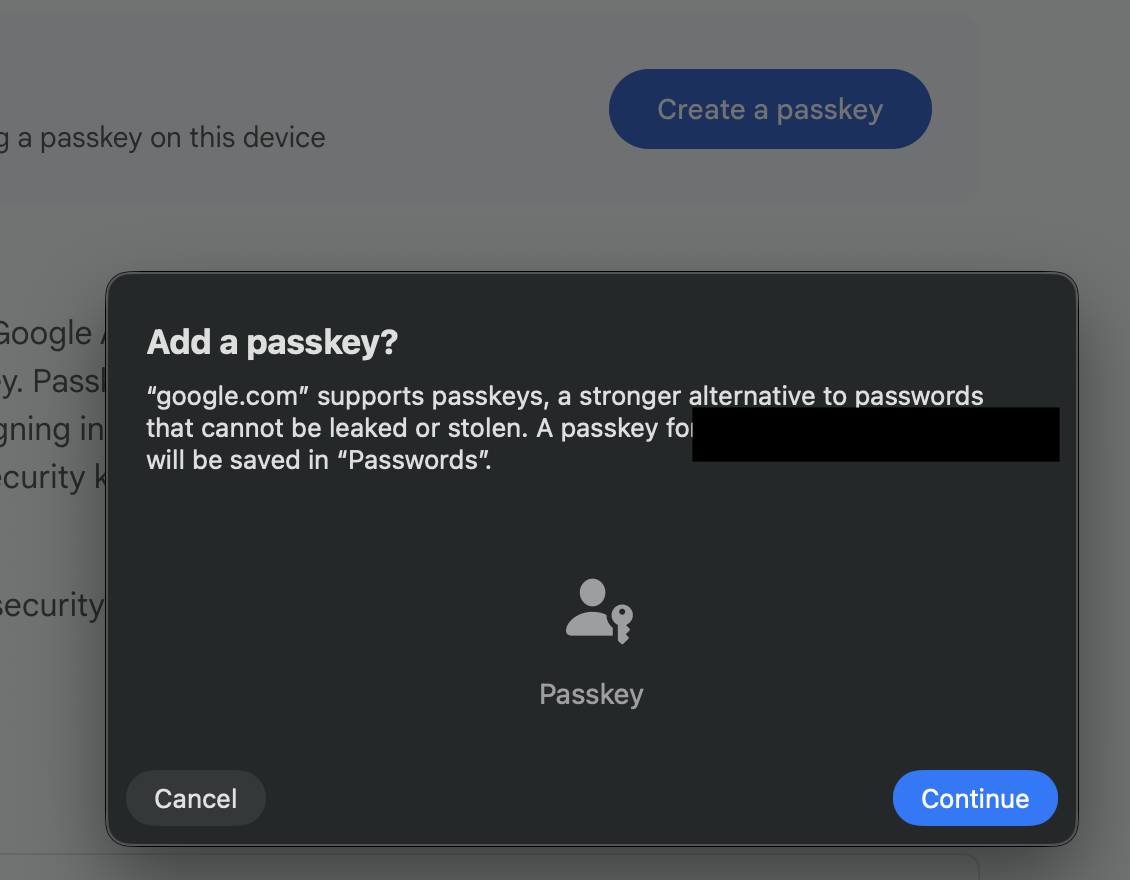

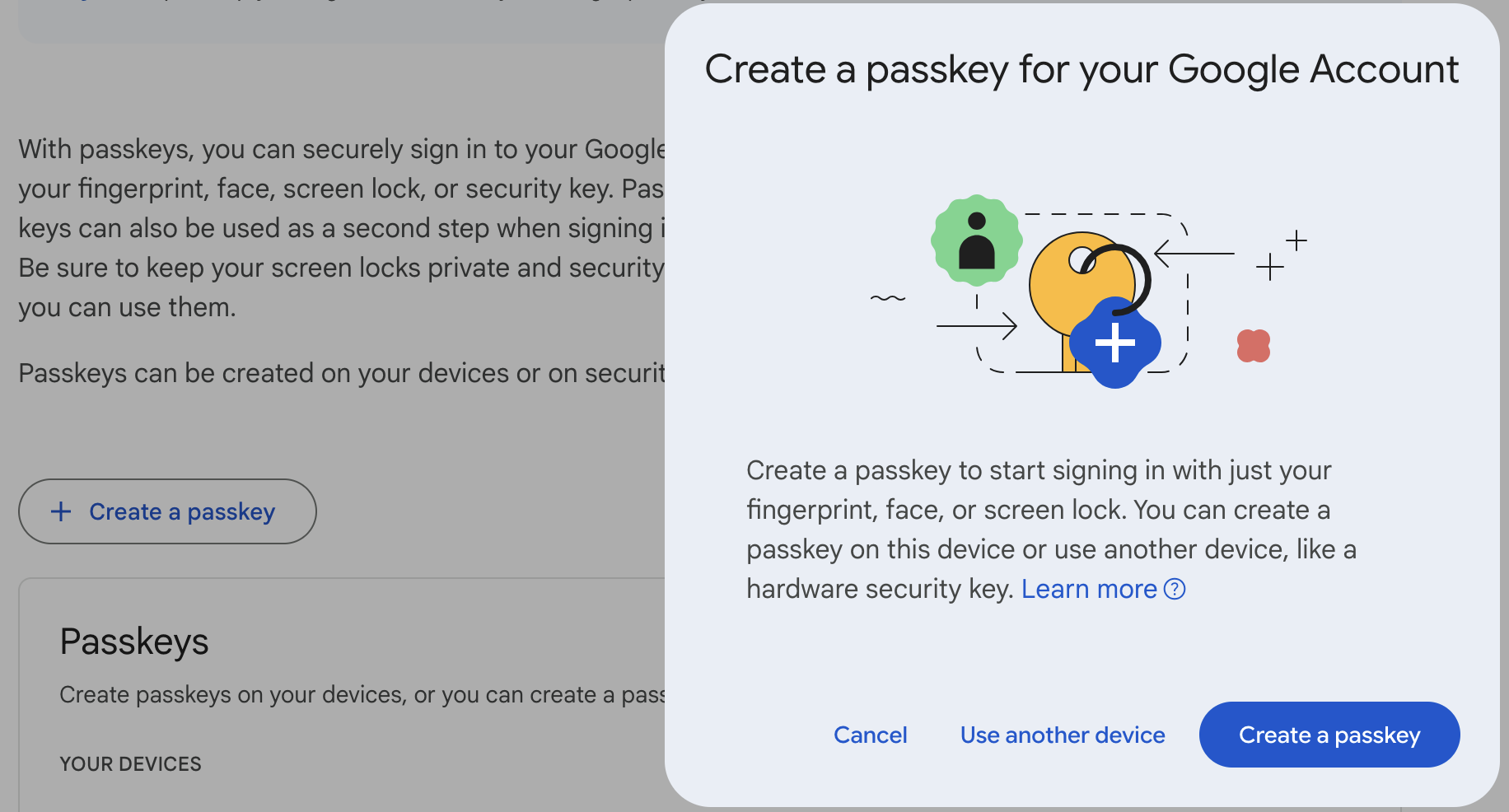

Even if the service accepts roaming authenticators, one has to be careful where to click: Google places two “Create Passkey” buttons on its page. Clicking the first - the bright blue one - brings up the platform authenticator dialog.

Using the second button - lower on the page with a white background - offers the choice to “Use another device” which is where the YubiKey can be registered.

I’m not exactly sure what’s going on here, or whether this behaves differently on non-Mac systems or in non-Firefox browsers. But it seems like a subtle nudge to get people to use a particular type of authenticator.

Lastly, the WebAuthn standard is worth a read: it is easily readable and clearly illustrates the different behaviors.

-

Interestingly, if you log in on a laptop, your phone can act as a roaming authenticator! ↩